|

Presented by |

|

|

THE UNITED FARMWORKERS UNION

By RIck Tejada-Flores

The United Farmworkers Union AFL-CIO (UFW) has a special place in the history of farm labor organizing. It is the only successful union ever established to defend the rights of those who grow and harvest the crops.

The people who created the UFW were aware of the long history of failed attempts to organize farmworkers. They know that whatever group was the poorest and most recent arrival to this country would end un in the fields. Starting in the nineteenth century, agricultural work has been done by Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Mexican workers, both recent immigrants, and in the case of the Mexicans, also descendants of those who live here under Mexican rule.

The people who created the UFW were aware of the long history of failed attempts to organize farmworkers. They know that whatever group was the poorest and most recent arrival to this country would end un in the fields. Starting in the nineteenth century, agricultural work has been done by Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Mexican workers, both recent immigrants, and in the case of the Mexicans, also descendants of those who live here under Mexican rule.

Early attempts to organize in the fields in the twentieth century included a sugar beet strike in 1903 in Oxnard by the Japanese Mexican Labor Association, and the strike in Wheatland, California, in 1913 by the Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the Wobblies.

During the teens and 1920s, there were many similar organizing attempts, some led by Communist unions; and others that erupted spontaneously But employers were not required to negotiate with their workers, and could fire them if they joined a union. There was even a specific crime, “criminal syndicalism” which made labor organizing illegal.

Farm workers during 1910 grape harvest in California. |

Older farmworkers who worked the fields for decades joined the grape strike. |

Mentor Fred Ross relaxes with Manuel Chavez and Dolores Huerta at 1962 NWFA founding convention. |

In 1936, the National Labor Relations Act took effect, giving most American workers the right to join unions and bargain collectively. In order to gain support from Southern politicians to pass the law, farmworkers were excluded from its protection.

In 1941 the United States and Mexican government started the bracero program, which brought thousands of Mexican nationals north to work in the fields in the U.S. Often, braceros were used to undercut domestic wages and break strikes, making it almost impossible to organize. The program was conceived to solve labor shortages during World War II, but was so popular with growers that it was extended until 1964.

All of these early attempts to organize in the fields relied on organizing techniques that had been developed to reach people like factory workers or skilled craftsmen. They didn’t take into account the seasonal nature of farm labor, the fact that many who worked in the fields had to move constantly in order to survive, and the huge labor surpluses and braceros that would allow employers to quickly replace anyone who went on strike.

What would become the United Farmworkers Union started out with a completely different approach to organizing. Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla had learned community organizing in the Community Service Organization (CSO), which was set up in Mexican American neighborhoods in California in the 1950s by Fred Ross. In CSO, organizers helped people with everyday problems – filling out tax forms, getting children into schools, studying for citizenship. They taught people that when they came together they could make positive changes in their lives. This same approach would now be tried in the fields.

From 1962 to 1965 Cesar Chavez and a small group of organizers traveled up and down California’s agricultural valleys, talking to people, holding house meetings, helping with problems, and inviting farmworkers to join their new organization. They didn’t call the National Farmworkers Association (NFWA) a labor union, because people had such bad memories of lost strikes and unfulfilled promises. It was a slow and tedious process.

Everything changed on September 8, 1965. On that day another farmworker group, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), struck the Delano table grape growers. Most of AWOC’s members were Filipinos who had come to the U.S. during the 1930s.

One week later the NFWA voted to join the strike. Among the joint leadership were Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and Gilbert Padilla from NFWA, and Larry Itliong, Andy Imutan and Philip Veracruz from AWOC.

The bracero program had ended in 1964, but even without the threat of braceros to break the strike, it was clear that the strikers would need powerful allies to overcome the resources of the grape growers.

The farmworkers wanted people to see their strike as something bigger and more dramatic — a battle for justice and human dignity. It became the cause, la causa! The strikers reached out to church groups and student activists. Both had been drawn to the civil rights struggles in the South, and both responded to the “David vs. Goliath” battle taking place in Delano. The public was also attracted to the farmworkers commitment to non-violence. Chavez saw non-violence as both a moral principle and a tactic. Under his leadership, the farmworkers movement would adopt non-violence as its guiding philosophy.

Striker arrested during 1973 grape strike. Photo: Rick Tejada-Flores |

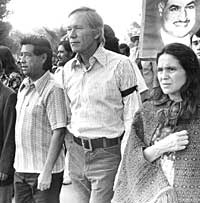

Cesar Chavez, Rep. Don Edwards and Dolores Huerta attend funeral for UFW member killed during 1973 grape strike. |

1975 March on Gallo Wine headquarters calling for union elections.

|

The famworkers also drew organized labor to their cause. Progressive unions like the UAW and AFSCME were early and lasting supporters, and countless union locals and members donated services and time. Even with this kind of help, it was a lopsided battle.

In 1966, the NFWA and AWOC merged to become the United Farmworkers Organizing Committee (UFWOC), shortly after Chavez led a 300 mile pilgrimage from Delano to the California state capitol, Sacramento.

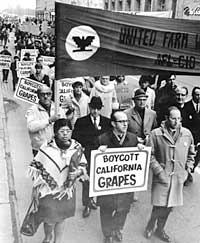

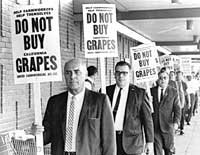

By 1967 farmworkers were enlisting consumers in their battle When the Giumarra Corporation tried to disguise their shipments by using other grape growers’ labels, the farmworkers began a national boycott of all table grapes. Striking farmworkers spread out across the country, forging alliances with students, churches, and consumers and other union members to try to stop the sale of grapes.

In 1968 Cesar Chavez decided to put his body on the line to revitalize the movement and dedicate it to non-violence. Inspired by the example of Gandhi in India, Chavez began a fast at the union headquarters in Delano. Thousands of farmworkers came every day to see him and participate in the evening masses. Robert Kennedy arrived to celebrate the end of the fast with Chavez. A few weeks later UFWOC endorsed Kennedy’s run for the presidency, and helped provide his margin of victory in the California primary. Although Kennedy was assassinated on the night of the California primary, the UFW had become a significant force in national politics.

Most of the farmworkers’ energy was focused on the grape boycott. At its height, more than 14 million Americans helped by not buying grapes. The pressure was irresistible, and the Delano growers signed historic contracts with UFWOC in 1969.

What had the farmworkers won? There was an end to the abusive system of labor contracting. Instead jobs would be assigned by a hiring hall, with guaranteed seniority and hiring rights. The contracts protected workers from exposure to the dangerous pesticides that are widely used in agriculture. There was an immediate rise in wages, and fresh water and toilets provided in the fields. The contracts provided for a medical plan, and clinics were built in Delano, Salinas and Coachella.

Because so many farmworkers worked for different growers in different areas, the usual system of union locals wouldn’t work in the fields. Instead, each ranch elected its own ranch committee. Each field office had its own service center to help members.

The signing of the grape contracts was a major victory for the fledgling union. But it was followed almost immediately by a new setback. The Salinas lettuce growers invited the Teamsters Union to represent their workers in order to keep UFWOC out. The Teamsters had the reputation of being one of the most corrupt unions in the country. Their contracts in Salinas were widely regarded as “sweetheart” contracts that weren’t intended to protect workers’ rights. There would be no hiring hall, no raise in wages, no pesticide protection. Lettuce workers were furious, and walked out on strike. Soon there was a new national boycott, this time of lettuce.

In 1972 UFWOC was finally accepted as a full member of the AFL-CIO, and changed its name to the United Farmworkers Union.

When the grape contracts expired in 1973, the grape growers followed the Salinas example and signed with the Teamsters Union. This triggered a series of strikes that started in Coachella and rolled up California’s San Joaquin valley . The AFL-CIO pledged full support and sent millions of dollars in aid. The Teamsters responded with crews of bikers and toughs hired in Los Angeles to intimidate and attack strikers. Thousands of farmworkers and supporters were jailed, and finally, two UFW strikers were killed on the picket line.

Grape boycott support march in Montreal, Quebec. |

White collar professionals march in support of grape boycott. |

Dolores Huerta holding Huelga ("strike") sign during first grape strike. |

The UFW called off the strike, and began to look for another way to guarantee workers the union of their choice. The answer was the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. It was supported by Governor Jerry Brown, who had worked closely with the farmworkers. The new law gave workers the right to secret ballot elections to chose a union, and required growers to bargain with unions that won elections.

In the elections that followed the UFW won an overwhelming series of victories, and the Teamsters withdrew from the fields.

Just when it seemed that the UFW's goals had been reached, things started to slip away. Growers dragged out negotiations for years, and used legal loopholes to slow the process down. Of the hundreds of elections that the UFW won from 1975 to 1980, less than half ever led to contracts. The law had ruled out the use of boycotts to win union representation, so the UFW couldn’t appeal for public support like it had done in the past.

The number of organizing drives and elections began to drop. Chavez and the UFW leadership put less and less emphasis on the fields, and more and more attention on reaching the American public. This time their preferred tool was computer generated direct mail.

In 1982 Republican George Dukmeijian was elected governor of California, and changed the agency responsible for enforcing the ALRA into a grower-friendly rather than worker-friendly agency.

The 1980's saw a decline in the UFW’s size, and its national significance. Cesar and the UFW concentrated on educating the public on the dangers of pesticides, both to consumers and farmworkers. The farmworkers built a network of radio stations, and created low cost housing for farmworkers. Although Chavez and Huerta remained, most of the union’s original leadership left or were forced out during the 1980s, because of disagreements on whether the union should continue to organize in the fields.

The death of Cesar Chavez in 1993 marked the end of an era, and the beginning of a new one. His successor, Arturo Rodriguez, has taken the union back to its roots in the fields, organizing and winning contracts in strawberries, mushrooms, and wine grapes.

The UFW has had a positive effect on the entire American labor movement. Their example in winning rights for the poorest and least-protected workers has inspired other unions to return to the task of continuing to organize. Many UFW organizers have applied their skills in new settings, such as the Justice for Janitors campaign developed by SEIU.

The UFW | Cesar Chavez Elegy | His Own Words | Timeline

|

|